News Archive - 2014-08 (August 2014)

2014-08-01 Criticism of Sweden's record-long detentions is growing

'Those two weeks were so far the worst in my life. Because I was heartbroken, I was afraid, I was worried, I did not know what lay ahead.'

- Andreas Nygren, today with an NGO helping minors in detention

'I'd very much prefer to be locked up with rats and bad food.'

- Göran, in pretrial detention for 850 days with no access to the outside world

Transcript: Göran sat in pretrial detention for 850 days - criticism of Sweden's record-long detentions is growing

Source: http://sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/392059?programid=4702

Program: In the Name of the Law

Radio channel: Swedish State Radio (sverigesradio.se)

Broadcast date: 6 July 2014

Original language: Swedish

Length: 29:32

Key:

Andreas Nygren: Processkedjan (NGO helping minors in detention)

Beatrice Ask: Minister for Justice

Bengt Holmgren: Psychologist

Elisabet Fura: Chief Justice Ombudsman

Elisabeth Lager: Legal Director, Swedish Prison and Probation Service

'Göran': Detained in isolation for 850 days (not his real name)

Göran Martinsson: Stockholm Police

Johnny Lind: Police Commissioner

Lars Bergman: Swedish Police Union

Lena Olsson: Left Party

Lasse Wierup: Presenter

Morgan Johansson: Social Democrat Party

Mattias Pleijel: Assistant Presenter

Nils Öberg: Swedish Correctional Service

Per Hedkvist: Prison and Probation Service Gotland detention official

Rickard Jonsson: Sweden Democrats (Right Wing Party)

Thomas Rolén: Head of the Administrative Court (Appeals division)

STARTS:

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Sweden should have a humane correctional system. So why are we one of the countries that can keep people detained indefinitely in extreme isolation? And why is it that many agree with the UN and other bodies who say that the system should be changed? And how is it that the issue is nevertheless politically dead? And why does no one know how often the correctional authorities decide on their own on isolation even after the courts have made a ruling that there shouldn't be isolation? Welcome to 'In the Name of the Law' with me, Lasse Wierup, Presenter.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: Our Swedish remand prisons were not designed for the detention periods that have evolved over time.

Beatrice Ask, Minister of Justice: There are rules for when restrictions are to be imposed and if they are followed it is reasonable.

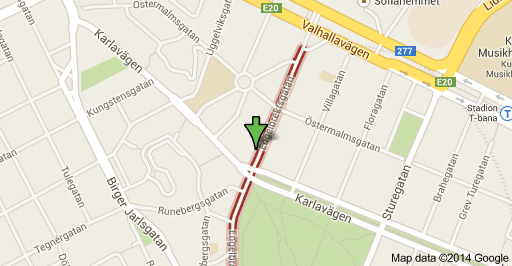

'Göran': I'd very much prefer to be locked up with rats and bad food. The window where I lived for nine months, it's the third to the far right there.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: We're standing in the park in front of Kronoberg remand prison in Stockholm. 31-year-old Göran lived up in the taller building.

'Göran': It's not a real life up there. People aren't evolved to be in isolation.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Göran - who is actually called something else - is one of the main characters in the largest narcotics trial ever in Sweden, where detention times have broken Swedish records. Göran was arrested in 2010 on suspicion of having attempted to coordinate a large shipment of cocaine in the Caribbean Sea.

'Göran': I come from an ordinary Swedish family. I've had all kinds of jobs. And I have lived on the wrong side of the law too. I've been convicted of grand larceny and aggravated robbery. Before this case that is.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Because the prosecutors believe that there is a risk that Göran will interfere with the investigation, the court permitted that so-called restrictions be imposed on him. This meant that he was not allowed to see anyone other than custody staff, his lawyer, and the police officers who interrogated him. He was not allowed any TV, radio, newspapers, or computer in his cell.

'Göran': Go into a toilet and lock the door. And sit there for 24 hours. Just try it. And don't make contact with anyone. You can't talk to anyone, you just sit there, and three times a day a small flap opens and food is tossed in. A completely bare room of 7m2 where you spend 23 out of 24 hours. Then you have an hour in which you are able to go up on the roof, and there are small 'pie slices' as they call them. You see them on the roof there.

Remand staff: This is what a cell looks like. We have a bed, a desk, a small stool, everything fastened to the walls and floors to prevent them from being thrown around. We have a small metal sink.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Restrictions are not uncommon, quite the opposite: they are the rule in most cases. Approximately 2 out of 3 people in pre-trial detention or about 6,000 people per year have restrictions imposed on them for varying periods of time.

Elisabet Fura: [3:14] I find it troubling when you see how often these long periods in custody are coupled with restrictions. They really are locked up for 23 hours a day, and that obviously does something to people, it affects them to be locked up like that.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [3:29] Elisabet Fura, head justice ombudsman, has previously sat on the bench of the European Court of Human Rights, and according to her, the correctional system has recently taken steps to imposing even harsher conditions by building so-called 'security jails'.

Elisabeth Fura, Justice ombudsman: There is a door that opens automatically, and you go into a corridor alone, monitored through cameras by a guard who is sitting in a completely different building looking at you as you go out and go through and go to this little pie slice where you get to wander around like a - well like a caged animal, then, for an hour, and then go back, and you have not met a single person in that whole time.

'Göran': When I tell friends and acquaintances how it works, so many of them look bewildered, asking 'What? Can it really be like that?'

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: Bengt Holmgren, I am a psychologist, I have worked as a consultant at Kronoberg remand prison in Stockholm.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Bengt Holmgren has met hundreds of people in detention and has studied how restrictions can trigger mental illness.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: Here is a sofa in the shade.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: In about 25% of the cases he has seen a connection. It seems that one can say that the isolation itself causes mental illness in the form of depression or anxiety and it remains as long as one has restrictions until these are lifted.

'Göran': One day you are in a panic and want to get out, the next you are depressed by everything, it's a real roller coaster. I got problems with my eyesight because you have a wall in front of you, just three feet in front of you all the time, so - it's a very unusual feeling indeed.

Remand prison staff: [05:14] Shutters have a small remote control so that they themselves can control. But that's when they do not have restrictions. If they have restrictions then they must not have any contact with the outside world.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: An important reason for the emergence of these questions about mental illness is that they do not know when the detention and restrictions will come to an end. If they knew that, it would be easier to cope with it, I think.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: 31-year-old Göran says that he recognises the what psychologist Bengt Holmgren is describing.

'Göran' [5:46] Had someone told me on the first day when I was sitting there that 'you will be there for one hundred days', it would have been hard. But then at least one would know! When a hundred days comes and goes, then two hundred, then four hundred, then six hundred, then eight hundred days, when one begins to wonder when will it end? And one has no clue!

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Unlike some countries - including France, Spain, and Denmark - Sweden has chosen not to have any upper limit to detention. Detention decisions can be extended indefinitely. Same thing with isolation.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [06:18] I have asked some police officers, what would it mean for you if you had a maximum of three months? And they answer: Well, we would have to work faster. They didn't act like they thought it would make their work impossible. Because as it stands now, there is no obligation to do things quickly.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [6:35] Psychologist Bengt Holmgren is not the only one who believes that Sweden should introduce an upper time limit.

Elisabeth Fura, Justice ombudsman: If you had such a provision, it would help the prosecutor and the police to be more effective in their investigations if they knew there was an upper limit.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Ombudsman Elisabeth Fura says that the judicial review process of extending detention is sometimes not as thorough as it should be. The review process is handled in a routine manner. Detention is the default just in case. Or the extension of the detention is erring on the side of caution.

'Göran': From the moment of my final interrogation to the trial date, several several hundred days went by. And on good days, I had no contact with the investigative unit at all, I just sat, well - in storage basically. It's amusing to compare my situation with the Swedish journalists Martin Schibbye and the other one who were imprisoned in Africa. They were imprisoned together. I much prefer a room with two hundred people and being locked up with a friend than to be in total isolation without seeing a single person. It's... Ah it's... Indescribable.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [7:40] The Council of Europe's Committee Against Torture has made five visits to Swedish remand prisons since 1991. Every time, the correctional system has been criticised. And it is precisely the frequent restrictions that were the object of criticism. The UN Committee against Torture has criticised Sweden on similar grounds and suggested measures to break the isolation practice. Ombudsman Elisabeth Fura again:

Elisabeth Fura, Justice ombudsman: [08:06] And each time, it becomes the... It gets embarrassing when nothing has happened [between visits], it just becomes an exercise of 'naming and shaming'.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: But really - has nothing happened at all? During Almedal Week [an annual festival of politics and current affairs] in Gotland the Correctional Service Chief Executive Director Nils Öberg has been invited to a seminar to talk about how he and his colleagues are dedicating resources to trying to help inmates get back to a better life. But when it comes to those sitting in detention, no resources are dedicated, whereas, according to Nils Öberg, they're needed.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [08:37] Yes, but I see it this way. My opinion is that our Swedish remand prisons are not designed for the detention periods that have evolved over time, ie periods of custody have become longer and longer. And that means a great pressure on the detainees, but also a great strain on the correctional authority which, because it is not meant to be that people sit in custody for such long periods of time, and certainly not with extensive restrictions. It is very difficult to manage this in a good way.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [9:14] The problem is, according to Correctional Service's Director General that the staff do not have time to socialise with the detainees or break the isolation in any other way.

Nils Öberg, Swedish Correctional Service: It is our job to do it, but often that competes with many other activities that our staff also have to do.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [09:30] One of the most serious problems is that it generates problems with one's ability to have an effective legal defence, in the sense that if you have suffered from depression or an anxiety disorder that you've had for so many months and then you are expected to go to trial and be able to defend yourself, then there it is a serious problem.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: What psychologist Bengt Holmgren is describing affected the detainee Göran. When the trial for drug smuggling finally began, he lost his temper with the prosecutor and erupted.

'Göran' (tape from hearing): I thought I'd just start by apologising because on a few occasions during this trial I have found it difficult to keep my mouth shut when perhaps it should have been.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: This is Stockholm District Court's own recording of the hearing where Göran appeals to the Court to be understanding.

'Göran' (tape from hearing): You become quite frustrated when you sit in isolation for 20 months, it's been over 300 days since the police interrogated me, and I hope as well that the court will have some kind of consideration that one is not always in one's best condition when one comes down here to the courtroom.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: Depression may bring a kind of feeling of resignation as well. One can, as it were, give up the very idea of why one should care.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Göran was not the only one of the defendants who was affected psychologically by the prolonged periods of custody.

[Recording:] I can not stand to sit in this jail anymore. I get treated... You discuss whether you should take an hour and a quarter to go for lunch or if you should take an hour and a half and put me in a cell full of drunks up there - so I do not give a damn about your wretched lunch.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: A 58-year-old man who was arrested with 1.4 tons of cocaine was about to break the Swedish pre-trial detention record of four years. The man was so tormented by his detention conditions that he was considering confessing to other offences in the hope that this would mean he would be transferred to a prison.

[Recording:] Now I want to know, prosecutors. Are you looking to accuse me of anything more than [fourteen years]?. Then I will confess it. I will confess exactly whatever you want. I want to know: if tomorrow I sign this declaration of satisfaction, does it mean that I am going to prison next week?

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [12:00] Restrictions are not just imposed in investigations of serious crimes, and those who are in isolation are not only adults. Even minors suspected of crimes have stringent restrictions imposed on them.

Andreas Nygren: You're scared, you're sad, you're heartbroken, angry, you are in a whirlwind, and especially if you are a child under eighteen. I'm Andreas Nygren, I come from Processkedjan. We have met and coached youth who are 16-17 years old who have been in detention for 3-4 months with restrictions.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Processkedjan is a voluntary organisation that seeks out kids who are between 15 and 21 who have been arrested by the police.

Andreas Nygren: Especially those who are in custody and have restrictions, and we follow them from there all the way to freedom.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Thanks to a partnership with the correctional service, the coaches obtain authorisation to visit youth with restrictions and help them overcome some of the isolation. That is the job that correctional services executive director Nils Öberg says his staff do not have time to do. Andreas Nygren who today is 36 was just 17 when he was arrested for the first time.

Andreas Nygren: [13:05] Those two weeks were so far the worst in my life. Because I was heartbroken, I was afraid, I was worried, I did not know what lay ahead. And there was really no one who came into the room and could talk to me about these thoughts. I also got a lot of insight about what I should have done with my life, but I did not know what I'd do with it, with those thoughts. I sat in isolation for almost six months in relation to my final conviction and at the time I wrote a diary, I wrote a diary every day I sat in there, and when I read that diary today, I realise how bad I was feeling. Because I was paranoid, I thought they had set up cameras in my cell, I was sometimes euphorically happy, and sometimes I was as low as you can get, and all this was a state of shock. And if you are sitting there as a child locked up with those thoughts, it breaks you down completely.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [13:54] This is a small group of people that get people interested or thinking about the issue or how should I put it: feel sorry for them.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Psychologist Bengt Holmgren again.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: It's a problem that the public in general terms are ignorant of, and in addition a little prejudiced about, who think that these people are in this situation because they have themselves to blame. And then they forget about the important principle that you are innocent until unless a guilty verdict is handed down, and so you should be treated accordingly.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Five years have passed since the European Council's Torture Committee last visited Sweden. At the time we received specific criticism for keeping minors in custody with restrictions, and a series of recommendations were submitted to Sweden. The Swedish government has followed one of these recommendations, and this means that the prosecutor's office each year must report the exact numbers of minors in custody. The figures show that there is a higher percentage of minors who are detained with restrictions than the general population on remand. 80% of all children arrested between the ages of 15 and 17 had restrictions imposed in 2012, or in real numbers: 97 people. That same year, Denmark, who had also received criticism from the Torture Committee, did not have a single minor in incommunicado detention.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [15:28] The former chief of Kronoberg remand prison used to say that this is a very important barometer of how things are in Sweden, how we treat the people who are detained here. I think he was quite right.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [15:32] The conversation with the psychologist Bengt Holmgren takes place during the political Almedalen Week in Visby, on a bench by the beach. A few hundred meters away, political party activities are ongoing.

Mattias Pleijel, Assistant Presenter: Politicians over here in Almedalen then - are they interested in this issue?

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: I think you should ask them if you get the chance.

Mattias Pleijel, Assistant Presenter: We'll do that a little later. Then we will also explain why a Swedish correctional institution may decide to keep a person in isolation month after month even though a court has said no to restrictions. But first some news in brief.

News: [15:54] The arrest of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange will be addressed in the Stockholm district court again on the 16th of July. Assange has been living at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London for over two years to ensure that he be released to Sweden where he is suspected of rape and is remanded in absentia. The public defenders find it unreasonable that he should continue to be detained for such a long time, whilst the prosecutors do not think it is possible to use such arguments as Assange chose to stay away.

[Unrelated news item relating to reforming the police force until 22:20]

Per Hedkvist: [22:24] When you lock up a person for so many hours a day, it affects a person mentally, that is obvious. My name is Per Hedkvist, I work as a correctional officer in Gotland. With our younger detainees, we have a requirement placed on us to do things to break the isolation for at least 2 hours a day.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [23:04] It is the courts who are responsible for deciding whether people should be arrested or not, and whether restrictions should be imposed. But when we have examined the conditions in the Swedish prison service, we have discovered that there are exceptions to this practice. Here's what psychologist Bengt Holmgren, who has worked for many years in the prison system, has to say.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: [23:20] There are cases where the court has decided to lift the restrictions, and yet you still sit there in seclusion because the custody officers have determined that there is a security justification.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: This was what happened to 31-year-old Göran who was detained in Sweden's largest narcotics trial. After 20 months, the Stockholm district court determined that it was no longer necessary to keep him under restrictions. Göran looked forward to socialising with other detainees and to receiving unsupervised visits. Instead, he received notice from the prison that he would be held in so-called seclusion, which in practice meant that the isolation continued. Now he did not even have the right to make a private phone call to his mother.

'Göran' [23:43] The decision by the court, it becomes totally ineffective. It's like a... So it is completely meaningless!

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [23:50] The decision was taken by an official at the remand prison who consulted with police and prosecutors. The reason was that the correctional services feared that there was a risk that Göran could plan new crimes from inside the detention center.

'Göran' [24:01] After the court lifted the restrictions against me - that was in September 2012 - I still sat in complete isolation until the 23rd of May 2013.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [24:10] What happened then was that the Svea Court of Appeal had ruled that his detention had become disproportionately long. After 850 days - or two years and four months - Göran was to be released, despite the fact that the trial was not yet over. From having been in total isolation due to the correctional service's estimations that that he was likely to reoffend, he was now free on condition that he surrendered his passport and reported regularly to the police station.

'Göran' [24:37] I urge all those people in the judicial system to try and sit one day - just one day - in solitary confinement.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: When were you last in a Swedish remand prison?

Beatrice Ask, Minister for Justice: Good question. It must have been at one of the police visits I've made when I'm out there every week and visit the police and then you often look in but, but... I have not been locked inside a remand prison. I have not.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: During the political week in Almedalen we sat down at a picnic table with Minister for Justice Beatrice Ask. She has followed the record-long detention periods in this and other recent cases, although she did not want to give us an opinion about whether 850 days isolation is reasonable or not.

Beatrice Ask [Justice Minister]: [25:14] Where specific restrictions are in place they must have been authorised, and then they are reviewed by a court continually as well, so I assume that they had a good reasons.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: The fact, that the Court's decision on restrictions can be replaced by the Correctional Service's internal isolation rules, appears to be news for the Minister of Justice.

Mattias Pleijel, Assistant Presenter: [25:28] And how common is this? That the correctional institution decides on total seclusion?

Beatrice Ask, Minister for Justice: I do not know offhand, but I am certain that the prison administration has accurate statistics on the matter.

Nils Öberg: [25:38] No I can not give you any statistics on it.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: We find Prison Service Director Nils Öberg in the crowd.

Nils Öberg: I do not know the statistics about how often this occurs off the top of my head.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Nils Öberg turns to his press secretary who promises to get back to us. But in the end we get no such statistics.

Nils Öberg's press secretary: We do not have that kind of statistical data.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Elisabeth Lager is the legal director at the Corrections Authority.

Elisabeth Lager: Every decision is taken on a case-by-case basis and that is why it is difficult to gather data on it.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: [26:01] But back to the question of whether Sweden should follow other countries and impose a maximum limit on detention. In Denmark, for example, six months of detention for offences that have up to 6 years prison sentence, and one year of arrest for offences that have still longer sentences. And now that we are here in Almedalen and have the opportunity to do a survey of all the parliamentary parties, we ask the question.

Johan Linander, Centre Party: Custody periods in Sweden are too long. I am Johan Linander, I am the legal spokesperson for the Centre Party. But the response from the Centre Party is still 'no' [to imposing upper limit].

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: KD, Folkpartiet, the Greens, and the Social Democrats give the same answer.

Morgan Johansson: It's very difficult to impose absolute deadlines.

Mattias Pleijel: But other countries do it.

Morgan Johansson: I know, but it's very hard to do!

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: The person saying that is Morgan Johansson, who is tipped to become Attorney General if the Social Democrats form the new government in the autumn elections.

Morgan Johansson: Many of those investigations are extremely complicated, so I'm not willing to make a statement unless I see a proper impact assessment.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Two parties, however, say yes.

Rickard Jonsson, Sweden Democrats: There must be a maximum time limit, that is my firm belief. People sit in limbo too long, often without any information. It is unworthy of a country like Sweden.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: The person who says that is the Sweden Democrats' Rickard Jonsson. And for once, his party agrees with the Left Party, if only on this one issue.

Lena Olsson, Left Party: Human rights must also apply to those suspected of crimes.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: And that was the Left Party's Lena Olsson. But the fact is that the issue in practice has already been addressed. At the beginning of the year, the Prosecution Authority presented an investigation of how Sweden should handle international criticism. And in this investigation, that the Minister of Justice hopes will lead to Sweden avoiding future criticism, no upper limit has been suggested.

Beatrice Ask, Minister for Justice: It has then been argued in the legal system that we achieve better results without upper limits to detention periods because then people would simply wait until they reach this limit, so such a reform would have a problematic effect.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Yes if you were to believe Justice Minister Beatrice Ask, the police would on the contrary risk having to work slower if an upper limit were introduced. Instead, she hopes for plea deals for those who do cooperate with the police, better evidentiary standards through earlier interrogations, and more resources for forensic work, an acknowledged bottleneck. It is also proposed that detainees be guaranteed two hours of human contact per day.

Mattias Pleijel: [28:29] Are other countries wrong in having an upper limit?

Beatrice Ask, Minister for Justice: They have a different way of thinking. That does not mean one is better than the other.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: One who is not convinced by the Prosecutor General's investigation is psychologist Bengt Holmgren who studied mental illness amongst detainees.

Bengt Holmgren, psychologist: The investigatory commissions from both the UN and the European Council - they of course agree that this is not good. That is to say, that it is harmful to do things this way. That should be sufficient reason to actually make more radical changes than what is proposed in this investigation.

Lasse Wierup, Presenter: Finally we can tell you that Göran, who appeared in our feature, was sentenced last week to prison for 6 years and 10 months. And that concludes 'In the Name of the Law' for this time.

(© and reprinted with permission from Assange in Sweden, where reprint requests should be directed. For further documents in the new case filing, including the initial petition to the Stockholm court and a facsimile of Marianne Ny's response to the court, see Justice4Assange.)

2014-08-11 Assange in Sweden: This Day Four Years Ago

Sunday 15 August 2010

What happens today is another of the official reasons Julian came back to Sweden. Today he's to meet Rick Falkvinge and sign an agreement for WikiLeaks hosting with Pirate Party rack space in the Bahnhof bunker.

Anna comes along as the official WikiLeaks press secretary.

Pirate Party system administrator Richie Olsson also tags along to photograph the event. One of his photographs was long suppressed; it's found below. It shows Anna beaming on the far left.

Saturday 14 August 2010 - Part Three

The crayfish at Anna's is to begin at 19:00; at least Johannes arrives late. The others at the party include fellow journalist Donald and:

- Kajsa Borgnäs, an officer of the Social Democrats and a friend of Anna's;

- Rick Falkvinge and another member of the Pirate Party, perhaps Anna Troberg;

- Alexandra Franzén, Kajsa's escort for the evening, formerly of the Swedish embassy in Ankara.

Anna takes Kajsa aside when the latter arrives and tells her it's 'fair game' to hit on Julian. And according to Donald, Anna plays up to the fact she has Julian under her roof.

'And she jokes about Julian, she says he's a special bloke. Suddenly he's just gone in the middle of the night and there he is sitting in the bathroom with his computer and... Uh, she's joking rather wildly in a fun way about that. And, and we, sometimes so, tell similar stories. But at the crayfish party uh, so she's sitting next to Julian and then she says, and so she brings it up, where did you go off to last night she says... And then she adds that, right on this theme as I say, uh, I was fucking proud, got the world's coolest guy in my bed and living in my flat.'

- Testimony of Donald Boström

Donald is really into crayfish and so doesn't pay much more attention to what's going on around.

'Well, the only possibly relevant... I can say I don't participate very much, I eat mostly, I love crayfish. (Laughs.) So I devote a lot of time to eating. But, uh, I know that they're talking about where Julian is going to sleep. Should he go back with this couple as planned. There's another one of Anna's friends, uh, and there's Anna. Uh, but I manage to understand it's already decided at the table Julian's going to stay with Anna again that night. Uh, without being a part of the discussion I understand that's how it's going to be, so that... Again so I'm one of the ones who left the earliest. And the others are still sitting there and...

- Testimony of Donald Boström

Johannes is more observant.

Uh, and so the evening wears on. Uh, and so I note a, a curious uh, exchange, one can say. It's a very hearty evening, I can say that like already at once.

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

It's Alexandra Franzén.

There's absolutely nothing, uh, hateful like or something like that, save for one thing. And it was then a friend of Anna Ardin's who sat quite a ways from me, uh, who made it very clear that partly she's a lesbian and partly had a, a very strong grudge towards men in general. Uh, and she says something like, she screams over the table to Anna that, uh, next time we'll have a crayfish party without men or something like that. So I just put that, that phrase in my memory. Then I asked a little half-joking like this, I spinned the issue further with, with Anna. Like this why would they want to do that. She said something like, yeah yeah but it's good when women can, can get together like only for themselves, be strong together or something like that.

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

Johannes also hears of Julian's new plans for the remainder of his stay in Sweden.

'Uh, and later on in the evening so, uh, I think I asked, uh, I asked Anna, um... No I first asked Julian, uh, where, where he would, would spend the night. Uh and, and then he says, yeah I have a few offers. OK, OK, but everything seemed like fixed. And, and so he says, well I've been invited by one of those young ladies who, who, we, who we met before, Sofia. But there was a technical detail or something like that to be arranged before they could meet. I don't know what that technical detail was, I wasn't very interested in that, I just wanted to know if he had somewhere to sleep. Because if, if I was going to let him use my flat or something like that. Uh, and then I asked Anna if it was OK if he stayed at her place instead or if she wanted me to take him to my place. Uh she said, no no problem, he can, sure he can stay with me.'

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

It's in the wee hours that Anna tweets out to the world.

'Sitting outdoors at 02:00 and hardly freezing with the world's coolest smartest people, it's amazing!'

- Tweet by Anna Ardin

Johannes is one of the last to leave the party. He stays and helps with the cleanup.

'Uh and then the hour was very late, perhaps three or something like that and so everyone left except Julian and, and Anna. I helped carry up the last, last glasses and stuff. And, and then I said farewell to them in the flat. And then it was apparent that, that they both would be sleeping in the flat.'

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

Saturday 14 August 2010 - Part Two

Julian's talk ends about noon; Peter's group will have to go out onto the grass outside to hold the Q&A as they hadn't paid for more time indoors. People assemble outside, with Sofia and Peter standing to one side and Johannes and Donald off to another, as Julian answers questions from the media. Both Johannes and Donald are concerned about the 'outsider' having close access to their select 'group', perhaps Johannes more than Donald.

'Uh, and, and so I ask who, something about yeah who, who is that. Uh, because she was standing too close, too close to the gang who'd organised the event. And so he says, no but she had, she's been helping here as, as a volunteer or an apprentice, something like that he said. Uh, OK I say, but you can see to it that she, that they leave. Because I mean I don't want any outsiders at our lunch. Uh, now it's been like everything from uh, politicians to journalists to like groupies who've been standing there for almost four hours. We can like go ourselves.'

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

It's decided the 'group' will go to lunch in the vicinity - to Bistro Boheme. In the 'group' are Julian, Anna, Peter, Johannes, Donald, and Sofia. They sit at the end of a table; clockwise it's Peter, Julian, Sofia at the end, Johannes, Anna, Donald. The only remarkable thing at the lunch, which Johannes picks up but Donald does not pick up, is Sofia's sole contribution to the conversation.

'Uh I noticed a really strange scene. Because she sat quiet through, through the entire lunch. She sat next to Julian. I think it was Peter, Julian, her, me, Anna, Donald. Uh, and she sat quiet during the entire lunch and nothing to chime in under, with the uh, in the topics we discussed. And sure enough, she broke into the conversation. And so she asked, she stared intently at Julian and so she asked, did you like, did you like your cheese sandwich or something like that. And I reacted, I don't remember if it was a cheese sandwich but it was something like that, something, something extraordinarily trivial. Uh and, and he reacted too. And he noticed she was sitting next to him. And so he looked at her, uh... And so he said, uh, yeah do you want to taste it? And so she took a bite of his cheese sandwich. Uh, and (laughs)... Yeah if you think if you're like sitting with a bunch of policemen like and then so there's someone there you don't really know who it is who takes a bite of your friend's cheese sandwich uh, you're a bit perplexed.'

- Testimony of Johannes Wahlström

It was suggested that Julian might enjoy a crayfish party. Johannes believes he suggested it, but Donald recalls Peter suggesting it. Anna makes a few calls and in a short while it's all arranged: party at 19:00 at Anna's.

Johannes, Julian, and Sofia leave together for Hötorget to find additional computer gear, but the shop they want is closed. Caught between an offer from Johannes to help him help his parents move furniture and an offer from Sofia to visit her place of work and perhaps take in a movie, Julian chooses the latter. They agree to meet later at Anna's for the party.

Saturday 14 August 2010 - Part One

Saturday is a long and eventful day. What happens today is one of the two official reasons Julian came back to Sweden. He'll first hold a speech on truth being the first casualty of war; and then, as things turn out, he'll attend a crayfish party for his benefit that goes on and into the 'wee hours'.

The morning starts with a knock on the door at Anna's flat in Tjurbergsgatan. It's Johannes Wahlström coming to call. An unofficial liaison between WikiLeaks and the Swedish media, Johannes is there, as he himself tells it, to make sure Julian finds the venue and gets there on time.

The door opens - and it's Anna standing there, not Julian, something that mildly shocks Johannes. As he himself tells it: 'My own flat's tiny, only 35 square metres, but this flat is even smaller, so how could two people...?'

But there they are, Anna and Julian, and Johannes whisks Julian off.

Anna will also be at the venue, as previously scheduled, together with Brotherhood boss Peter Weiderud. The venue has limited capacity, and all the seats have already been spoken for, with priority being given to accredited members of the media.

There's one exception to the above rule: a part-time museum curator and hopeful photographer will somehow get a ticket as late as the day before, without the requested accreditation. Her name? Sofia Wilén. Sofia's from the city of Enköping, northwest of Stockholm, beyond the capital's city limits.

Sofia comes dressed in a shocking pink jumper, something that puts both Johannes and Donald (Boström) off. Not that they dislike the jumper or the colour, but more that they think such attire is not suitable for the event or for their profession.

Sofia has the opportunity for an interchange with Julian before the talk, volunteering to go off on the town to fetch a computer cable.

Sofia takes a seat to the right (stage left) in the front row; her motorised camera can be heard clicking throughout the talk.

The complete talk is still online.

Friday 13 August 2010

Julian starts using Anna's flat on Thursday 12 August. The flat is at his disposal through the talk ('seminar') on Saturday morning, when Anna is to return. Rick Falkvinge is to arrange for Julian's accommodations at that point.

But something happens today: in late afternoon or early evening, Anna returns unexpectedly.

Anna's flat isn't spacious. Most flats on the island of Södermalm are small; Anna's flat measures 25 square metres (approximately five paces by five paces). Including cooking area and water closet, the flat doesn't have room for much more furniture than a minimal bed.

This Friday afternoon is also in the middle of Sweden's white collar holiday month. Many of the city's residents are away, many businesses are closed, and those who can't leave town are on their way by now to their summer cottages for the weekend. A Friday afternoon in August is hardly the time for a stranger to go looking for emergency accommodations.

Anna suggests she and Julian go out to dinner to discuss his sudden predicament. Over dinner, Anna persuades Julian to stay in the flat with her. According to both Anna and Julian, they make love when they return from the restaurant.

Wednesday 11 August 2010

Julian Assange arrives in Stockholm. He's to have dinner later that evening at the Beirut Café in Engelbrektsgatan in the north of inner city Stockholm.

Swedish freelance photojournalist Donald Boström and his girlfriend are at the dinner, along with a writer from the US and his companion for a European trip.

Donald has the keys to a flat on Tjurbergsgatan on Södermalm in Stockholm that belongs to Anna Ardin. Anna's the organiser of Julian's talk ('seminar') that coming Saturday, but she left town for the island of Gotland and left her keys with Donald.

Anna and Donald had reportedly not known each other before. Donald's the one who in 2009 unwittingly created the Swedish diplomatic crisis with Israel.

The original idea was to put Julian up in one of Stockholm's expensive hotels, but Anna's group, the social democratic Brotherhood, had a limited budget, and they'd heard that Julian preferred to not live in hotels anyway.

Anna was scheduled to return to Stockholm on the morning of Saturday 14 August; Julian was also scheduled to meet that same day with Rick Falkvinge, founder of Sweden's famous Pirate Party, to seal a deal for use of Pirate Party rack space by WikiLeaks in ISP Bahnhof's famous bunker under the White Mountains. Starting after the talk on Saturday, Julian's accommodations are to be taken care of by Rick Falkvinge and his fellow pirates.

The companion of the writer talks with Julian about her dissatisfaction with her trip; when she goes outside to smoke, Julian accompanies her. The writer follows out after a while, objecting to their leaving the dinner. The girl grabs Julian's hand and the two walk off into the night.

(© and reprinted with permission from Assange in Sweden, where reprint requests should be directed. For further documents in the new case filing, including the initial petition to the Stockholm court and a facsimile of Marianne Ny's response to the court, see Justice4Assange.)

2014-08-16 Statement of the Government of the Republic of Ecuador on the asylum request of Julian Assange

On June 19, 2012, the Australian citizen Julian Assange, showed up on the headquarters of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, with the purpose of requesting diplomatic protection of the Ecuadorian State, invoking the norms on political asylum in force. The requester has based his petition on the fear of an eventual political persecution of which he may be a victim in a third State, which can use his extradition to the Swedish Kingdom to obtain in turn the ulterior extradition to such country.

The Government of Ecuador, faithful to the asylum procedure, and attributing the greatest seriousness to this case, has examined and assessed all the aspects implied, particularly the arguments presented by Mr Assange backing up the fear he feels before a situation that this person considers as a threat to his life, personal safety and freedom.

It is important to point out that Mr Assange has made the decision to request asylum and protection from Ecuador because of the accusations that, according to him, have been formulated for supposed "espionage and betrayal" with which the citizen exposes the fear he feels about the possibility of being surrendered to the United States authorities by the British, Swedish or Australian authorities, thus it is a country, says Mr Assange, that persecutes him because of the disclosure of compromising information for the United States Government. He equally manifests, being "victim of a persecution in different countries, which derives not only from his ideas and actions, but from his work by publishing information compromising the powerful ones, by publishing the truth and, with that, unveiling the corruption and serious human rights abuses of citizens around the world".

Therefore, for the requester, the imputation of politic felonies is what backs up his request for asylum, thus in his criteria, he faces a situation that means to him an imminent danger which he cannot resist. With the purpose of explaining the fear he has of a possible political persecution, and that this possibility ends up turning into a situation of impairment and violation of his rights, with risk for his integrity, personal security and freedom, the Government of Ecuador considered the following:

- That Julian Assange is a communication professional internationally awarded for his struggle on freedom of expression, freedom of press and human rights in general;

- That Mr Assange shared with the global population privileged documented information that was generated by different sources, and that affected officials, countries and organizations;

- That there are serious indications of retaliation by the country or countries that produced the information disclosed by Mr Assange, retaliation that can put at risk his safety, integrity and even his life;

- That, despite the diplomatic efforts carried out by the Ecuadorian State, the countries from which guarantees have been requested to protect the life and safety of Mr Assange, have denied to provide them;

- That, there is a certainty of the Ecuadorian authorities that an extradition to a third country outside the European Union is feasible without the proper guarantees for his safety and personal integrity;

- That the judicial evidence shows clearly that, given an extradition to the United States, Mr Assange would not have a fair trial, he could be judge by a special or military court, and it is not unlikely that he would receive a cruel and demeaning treatment and he would be condemned to a life sentence or the death penalty, which would not respect his human rights;

- That, even when indeed Mr Assange has to respond to the investigation open in Sweden, Ecuador is aware that the Swedish prosecutor's office has had a contradictory attitude that prevented Mr Assange from the total exercise of the legitimate right to defense;

- That Ecuador is convinced that the procedural rights of Mr Assange have been infringed during that investigation:

- That Ecuador has verify that Mr Assange does not count with the adequate protection and help that he should receive from the State of which he is a citizen;

- That, according to several public statements and diplomatic communications made by officials from Great Britain, Sweden and the United States, it is deduced that those governments would not respect the international conventions and treaties and would give priority to internal laws of secondary hierarchy, contravening explicit norms of universal application; and,

- That, if Mr Assange is reduced to preventive prison in Sweden (as it is usual in that country), it would initiate a chain of events that will prevent the adoption of preventive measures to avoid his extradition to a third country.

Accordingly, the Ecuadorian Government considers that these arguments back up Julian Assange's fears, thus he can be a victim of political persecution, as a consequence of his determined defense to freedom of expression and freedom of press, as well as his position of condemn to the abuses that the power infers in different countries, aspects that make Mr Assange think that, in any given moment, a situation may come where his life, safety or personal integrity will be in danger. This fear has leaded him to exercise his human right of seeking and receiving asylum in the Embassy of Ecuador in the United Kingdom.

Article 41 of the Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador defines clearly the right to grant asylum. Regarding those dispositions, the rights to asylum and shelter are fully recognized, according to the law and international human rights instruments. According to such constitutional norm:

People who are in a situation of asylum and shelter will enjoy special protection that guarantees the full exercise of their rights. The State will respect and guarantee the principle of no return, aside from humanitarian and judicial emergency assistance.

Moreover, the right to asylum is recognized in the Article 4.7 of the Organic Law of Foreign Service of 2006, which determines the faculty of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Integration of Ecuador to know the cases of diplomatic asylum, according to the laws, the treaties, the rights and the international practice.

It is important to outline that our country has outstood over the last years for welcoming a huge number of people who have requested territorial asylum or refuge, respecting with no restriction the principle of no return and no discrimination, while adopting measures towards granting the refugee status in an efficient way, bearing in mind the circumstances of the requesters, most of them Colombians escaping the armed conflict in their country. The High Commissioner of the United Nations for Refugees has praised Ecuador's refugee policy, and has highlighted the meaningful fact that these people have not been confined to refugee camps in this country, but they are integrated to society, in full enjoyment of their human rights and guarantees.

Ecuador states the right to asylum in the universal brochure of human rights and believes, therefore, that the effective application of this right requires the international cooperation that our countries can provide, without which its enouncement would be unfruitful, and the institution would be completely ineffective. For these reasons, and bearing in mind the obligation that all the States have assumed to collaborate in the protection and promotion of Human Rights, as it is established in the United Nations Charter, invites the British Government to provide its contingent to reach this purpose.

For those effects, Ecuador has been able to verify, in the course of analysis of the judicial institutions regarding the asylum, that to the confirmation of this right attend fundamental principles of general international law, which because of their importance have universal value and scope, for they are consistent with the general interest of the international community as a whole, and count with the full recognition of all the States. Those principles, which are contemplated in the different international instruments, are the following:

- The asylum in all its forms is a fundamental human right and creates obligations erga omnes, meaning, "for all", the States.

- The diplomatic asylum, the refuge (territorial asylum), and the right to not being extradited, expulsed, surrendered or transferred, are comparable human rights, thus they are based on the same principles of human protection: no return and no discrimination with no distinction of unfavorable character for reasons of race, color, sex, language, religion or belief, political or other type of opinions, national or social origin, birth or other condition or similar criteria.

- All these forms of protection are ruled by the pro homine principles (meaning, most favorable to the human being), equality, universality, indivisibility, complementarity, and inter dependency.

- The protection is produced when the State which grants the asylum, refuge or requested, or the protective potency, considers that there is a risk or fear that the protected person may be a victim of political persecution, or are charged with political felonies.

- It corresponds to the State which grants the asylum to qualify the causes of asylum and, in the case of extradition, to value the evidences.

- Regardless of the modality or form in which it is presented, the asylum has always the same cause and the same legal object, meaning, political persecution, which is a legal cause; and to safe guard the life, personal safety and freedom of the protected person which is a legal object.

- The right to asylum is a fundamental human right; therefore, it belongs to the ius cogens, meaning, the system of imperative norms of right recognized by the international community as a whole, which does not admit a contrary agreement, annulling the treaties and dispositions of international law against it.

- In the unforeseen cases on the law in force, the human being is under the safe guard of the humanity principles and the demands of the public conscience or under the protection and empire of the principles of the law of people derived from the established uses, of the humanity principles and the dictates of the public conscience.

- The lack of international convention or internal legislation of the States cannot be legitimately claimed to limit, impinge or deny the right to asylum.

- The norms and principles that rule the rights to asylum, refuge, no extradition, no surrender, no expulsion and no transference are convergent, to the necessary extent to perfect the protection and providing it with the most efficiency. In this sense, the international bill of human rights, the right to asylum and refuge and the humanitarian law are complementary.

- The rights of protection to the human being are based on ethical principles and values universally admitted and, therefore, they have a humanitarian, social, solidarity, assistant and pacific character.

- All the States have the duty to promote the progressive development of the international bill of human rights through effective national and international laws.

Ecuador considers that the right applicable to Mr Julian Assange's case is integrated by the whole principles, norms, mechanisms and procedures foreseen on the international instruments of human rights (regional or universal), which contemplate among their dispositions the right to seek, receive and enjoy asylum for political reasons; the Conventions that regulate the right to asylum and the right of refugees, and that recognize the right to not be surrendered, returned or expulsed when there are founded fears of political persecution; the Conventions that regulate extradition and that recognize the right to not be extradited when this measure can mask political persecution; and the Conventions that regulate the humanitarian right, and that recognize the right not to be transferred when there is a risk of political persecution. All these modalities of asylum and international protection are justified by the need to protect this person of an eventual political persecution, or a possible imputation of political felonies and/ or felonies connected to these last ones, which, to Ecuador's judgment, not only would put at risk the life of Mr Assange, but would also represent a serious injustice committed against him.

It is undeniable that the States, having contracted with so numerous and substantive international instruments - many of them judicially binding - the obligation to provide protection or asylum to people persecuted for political reasons, have expressed their will to establish a judicial institution of protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, founded as a right in a generally accepted practice, which gives those obligations an imperative character, erga omnes that, being bonded to respect, protection and progressive development of human rights and fundamental freedoms, are a part of the ius cogens. Some of those instruments are mentioned bellow:

- United Nations Charter of 1945, Purposes and Principles of the United Nations: obligation of all the members to cooperate in the promotion and protection of human rights;

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948: the right to seek and enjoy asylum in any country, for political reasons (Article 14);

- American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man of 1948: the right to seek and enjoy asylum in any country, for political reasons (Article 27);

- Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949, regarding the Due Protection of Civilians in War Times: in no case it is due to transfer the protected person to a country where they can fear persecutions because of their political opinions (Article 45);

- Convention on the Refugees Statute of 1951, and its New York Protocol of 1967: forbids to return or expulse refugees to countries where their life and freedom may be in danger ( Article 33.1);

- Convention on Diplomatic Asylum of 1954: the State has the right to grant asylum and to qualify the nature of the felony or reasons of persecution (Article 4);

- Convention on Territorial Asylum of 1954: the State has the right to admit in its territory people it judges convenient (Article 1), when they are persecuted for their beliefs, opinions or political filiations, or by actions that may be considered political felonies (Article 2), not being able the asylum granting State, to return or expulsed the asylum seeker that is persecuted for political reasons or felonies (Article 3); in the same way, the extradition does not proceed when it is about people who, according to the required State, are persecuted for political felonies, or for common felonies that are committed with political purposes, nor when the extradition is requested obeying political motives (Article 4);

- European Extradition Treaty of 1957: forbids the extradition if the requested Part considers that the felony imputed has a political character (Article 3.1);

- 2312 Declaration on Territorial Asylum of 1967: establishes the granting of asylum to the people that have such right according to Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including people who fight against colonialism (Article 1.1). The denial of admission, expulsion or return to any State where they can be object of persecution is forbidden (Article 3.1);

- Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties of 1969: establishes that the norms and imperative principles of general international right do not admit a contrary agreement, being null the treaty that at the moment of its conclusion enters in conflict with one of these norms (Article 53), if a peremptory norm of the same character arises, every existent treaty that enters in conflict with that norm is null and ended (Article 64). As far as the application of these articles, the Convention authorizes the States to demand their accomplishment before the International Court of Justice, with no requisition of conformity by the demanded State, accepting the tribunal's jurisdiction (Article 66 b). The human rights are norms of the ius cogens.

- American Convention on Human Rights of 1969: the right to seek and receive asylum for political reasons (Article 22.7);

- European Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism of 1977: the required State has the faculty to deny extradition when there is danger of persecution or punishment of the person for their political opinions (Article 5);

- Inter American Convention for Extradition of 1981: the extradition does not proceed when the requested has been judge or condemned, or is going to be judge before an exception tribunal or ad hoc in the required State (Article 4.3); when, with arrangement to the qualification of the required State, it deals with political felonies, or connected felonies or common felonies persecuted with political purposes; when from the case's circumstances, can be inferred that the persecuted purposes is mediated for considerations of race, religion or nationality, or that the situation of the person is at risk of being aggravated for one of those reasons (Article 4.5). The Article 6 disposes, regarding the Right to Asylum, that "none of the exposed in the present Convention may be interpreted as a limitation to the right to asylum, when this proceeds".

- African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights of 1981: the right of the persecuted individual to seek and obtain asylum in other countries (Article 12.3);

- Cartagena Declaration of 1984: recognizes the right to refuge, to not being rejected in the borders and to not being returned;

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union of 2000: establishes the right to diplomatic and consular protection. Every citizen of the Union may seek refuge, in the territory of a third country, in which the Member State of nationality is not represented, to the protection of diplomatic and consular authorities of any member State, in the same conditions of the nationals of that State (Article 46).

The Government of Ecuador considers important to outline that the norms and principles recognized in the international instruments mentioned, and in other multi lateral treaties, have preeminence over the internal laws of the States, thus such treaties are based in a universally oriented normative by intangible principles, from which a greater respect is derived, guarantee and protection of human rights against unilateral attitudes of the same States. This would subtract efficiency to the international law, which otherwise has to be strengthen, so the respect of fundamental rights is consolidated in function of integration and ecumenical character.

On the other hand, since Julian Assange requested political asylum to Ecuador, dialogues of high diplomatic level have been held, with the United Kingdom, Sweden and the United States.

In the course of these conversations, our country has appealed to obtain from the United Kingdom the strictest guarantees so Julian Assange faces, with no obstacles, the judicial process open in Sweden. Such guarantees include that, once treated his legal responsibilities in Sweden, he would not be extradited to a third country; this is, the guarantee that the specialty figure will not be applied. Unfortunately, and despite the repeated exchanges of texts, the United Kingdom never gave proof of wanting to achieve political compromises, limiting to repeat the content of the legal texts.

Julian Assange's lawyers requested the Swedish justice to take statements of Julian Assange in the premises of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. Ecuador translated officially to the Swedish authorities its will to facilitate this interview with the purpose of not intervening or obstacle the judicial process that is carried out in Sweden. This is a perfectly legal and possible measure. Sweden did not accept it.

On the other hand, Ecuador searched the possibility that the Swedish Government would establish guarantees to avoid the onward extradition of Assange to the United States. Again, the Swedish Government rejected any commitment on that sense.

Finally, Ecuador directed a communication to the Government of the United States to know officially its position on the Assange's case. The consults referred to the following:

- If there is a legal process in course or the intention to carry out such process against Julian Assange and/ or the founders of the WikiLeaks organization;

- In the case of the above being truth, what kind of legislation, in which conditions and under which maximum penalties would those people be subjected;

- If there is the intention of requesting the extradition of Julian Assange to the United States.

The answer of the United States has been that they cannot offer information on the Assange's case, with the allegation that it is a bilateral matter between Ecuador and the United Kingdom.

With these antecedents, the Government of Ecuador, faithful to its tradition to protect those who seek shelter in its territory or in the premises of its diplomatic missions, has decided to grant diplomatic asylum to the citizen Julian Assange, on the basis of the request presented to the President of the Republic, through a written communication dated in London on June 19, 2012, and complemented by a communication dated in London on June 25, 2012, for which the Ecuadorian Government, after carrying out a fair and objective assessment of the situation exposed by Mr Assange, attending his own sayings and argumentations, intakes the requester's fears, and assumes that there are indications that allow to assume that there may be a political persecution, or that such persecution may be produced if the opportune and necessary measures are not taken to avoid it.

The Government of Ecuador has the certainty that the British Government will know how to value the justice and rectitude of the Ecuadorian position, and in consistency with these arguments, trusts that the United Kingdom will offer as soon as possible the guarantees or safe conducts necessaries and pertinent to the situation of the asylum requester, so their Governments can honor with their actions the fidelity they owe to the international laws and institutions that both nations have contribute to shape along their common history.

It also trusts to maintain inalterable the excellent bonds of friendship and mutual respect that unite Ecuador and the United Kingdom and their respective people, confident as they are in the promotion and defense of the same principles and values, and because they share similar concerns about democracy, peace, Good Living, which can only be possible if the fundamental rights of all people are respected.