2011-07-20 Negotiating democracy – backdoor talks on Burma’s democratization revealed #cablegate #wikileaks

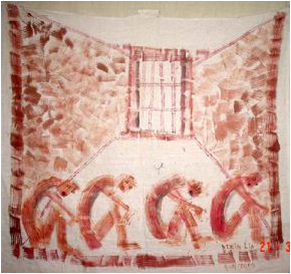

During the 7 years Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma's world renowned pro-democracy dissident, was under her second house arrest - from 2003 through 2010 - nothing was publicly known about the diplomatic efforts to promote democracy between the international community and the Burmese military dictatorship.

The U.S. and European states imposed economic sanctions to pressure the regime, and ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) member countries publicly denounced Burma without meaningful results. Recently released Southeast Asian cables by WikiLeaks, along with cables from India and China, provide a clearer picture of international efforts - from the frank reluctance of ASEAN member countries to push the Burmese regime in private talks to reports from inside-Burma.

Burma: NDL leadership expel competent young pro-democracy members, while the regime’s ‘economic patronage network’ remains firm

Aung San Suu Kyi is nothing more than a ‘symbol’; real moves toward democracy grow from the very grass-root levels

08RANGOON557 reports on the main obstacles to Burma’s democratization, while debunking common beliefs. The cables reveal that alleged frictions between regime leaders bore little importance. While small disagreements existed, they were aware that ‘if they do not stand together, they will fall together’, and consequently forced to obey the then dictatorial leader, Than Shwe, on critical decisions. (Shwe was deposed from the position and personally designated Thein Sein as a successor in March, this year).

Rumors of splits at the top of the regime are the result of uninformed analysis and wishful thinking of the exiles and outside observers. While the senior generals may disagree from time-to-time amongst themselves (as witnessed after Nargis), they follow the orders of Than Shwe. The senior generals are keenly aware that if they do not stand together, they will fall together.

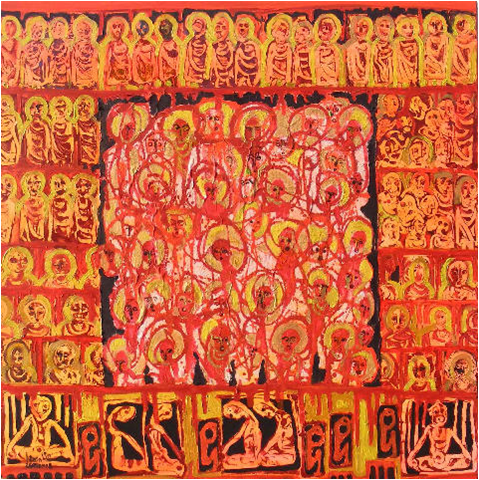

Another myth concerns the power of Aung San Suu Kyi as an effective democratization force in the country. The embassy pol/couns chief disagrees: although she remains a respected symbol of democracy, NLD's (National League for Democracy) role as a main actor for the pro-democracy movement has significantly shrunk. According to the cable, the reason stems from the inflexible and quite conservative ‘Uncles’, the leadership of the party; who criticized other leaders of the pro-democracy demonstration in 2007. The 2007 protests were recorded as a biggest pro-democracy demonstrations in 20 years:

Without a doubt, Aung San Suu Kyi remains a popular and beloved figure of the Burmese majority, but this status is not enjoyed by her party. Already frustrated with the sclerotic leadership of the elderly NLD “Uncles”, the party lost even more credibility within the pro-democracy movement when its leaders refused to support the demonstrators last September, and even publicly criticized them.

According to the cables, the ‘Uncles’ eliminated members they believe were 'too active', including young figures who flamed grass-roots sentiment or challenged the regime’s human rights abuse and corruption. They also stuck to a strictly hierarchical structure, which hindered progress with time-wasting talks on abstract policies and prevented young members from taking initiative to promote more creative and effective methods:

The Party is strictly hierarchical, new ideas are not solicited or encouraged from younger members, and the Uncles regularly expel members they believe are “too active.” NLD youth repeatedly complain to us they are frustrated with the party leaders. … The “Uncles” have repeatedly rebuffed the most dynamic and creative members of the pro-democracy opposition, who reinvigorated the pro-democracy movement throughout 2006 and 2007 by strategically working to promote change through grass-roots human rights and political awareness and highlighting the regime’s economic mismanagement. … Instead, the Uncles spend endless hours discussing their entitlements from the 1990 elections and abstract policy which they are in no position to enact. … Additionally, most MPs-elect show little concern for the social and economic plight of most Burmese, and therefore, most Burmese regard them as irrelevant.

India: Burmese regime is illegitimate, but useful – Burma as a practical tool in fighting north-east separatist movements

07NEWDELHI847 provides a clear view of the Indian government's stance on democratization efforts in Burma. India views the current regime as a highly useful political and economic tool, and idea the Indian government is reluctant to give up. The reasons include India's conflict with the ULFA (United Liberation Front of Asom, a group in north-east region insisting on separation from India) and Burma as sole gateway to ASEAN markets:

He asserted that Burma was an essential part of the GOI's two-pronged approach to tackling its insurgency problem in the northeast. The first element of the strategy is military, and "Burma is the only one helping us." Pointing to alleged Bangladesh unwillingness to confront Indian insurgent groups camped on its borders, Kumar argued, "Tell Bangladesh to cooperate and I am happy to say bye-bye Myanmar." Referring to the second approach, Kumar stated that "Bangladesh's stubbornness in allowing access to transit routes for trade leaves us with Burma as the only alternative to connect the northeast to ASEAN markets," and provide an economic incentive for ULFA to lay down its arms. "Do you want us to connect through China?" he asked.

According to the cable, India prefers the status quo, and is well aware that it is backing a regime internationally recognized as illegitimate:

PolCouns pushed back, noting that the Burmese junta was using its military might to violently repress innocent civilians. He also warned that India may experience a strong backlash for supporting the junta when a legitimate Burmese government comes to power. Kumar acknowledged that the possibility was a GOI concern.

For more information on the stance of the government of India on Burma in this article published by The Hindu.

Singapore: Burma is a battlefield of China-India power game, let alone the democratization

Singapore is a key ASEAN member. Burma's acceptance into the coalition is regarded as precious cover for the country's supposed legitimacy, therefore ASEAN pressure on the regime has always been regarded as one of the most important diplomatic pressures.

Singapore has lead the public denouncement of Burma's human rights abuses and in particular the political persecution of Aung San Suu Kyi. In 07SINGAPORE1932, Singapore’s Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew flatly expresses regrets in accepting Burma as a ‘new member’ of ASEAN, blaming member states' traditionally shared ‘antipathy to Communism'. Regarding the democratization process in Burma, he talks in an ambiguous manner: “It will be a long process,” he says. Instead of providing active solution, the Minister comments that Burma is a battle ground for China and India, where both have a vast economic interests:

He asserted that China had the greatest influence over the regime and had heavily penetrated the Burmese economy. China was worried that the country could "blow up" which would endanger its significant investments, pipelines, and the approximately two million Chinese estimated to be working in the country. India was worried about China's influence in Burma and was engaged with the regime in an attempt to minimize China's influence.

Cambodia: Burma Caucus, a public anticlimax

Cambodia, one of the three new members of ASEAN - along with Laos, Vietnam and Burma, has also been reluctant to make a public denouncement. The Burma Caucus was inaugurated in August 2006 to discuss the democratization of Burma in Cambodia but received scant support from officials of the ruling CPP (Cambodian People's Party). After a reported letter from the Burmese regime (06PHNOMPENH1534) protesting the establishment of the Burma Caucus and the Cambodian government's invitation to NLD MPs to join the launch which referred to Burma's democratic activists as "terrorists”, the Prime Minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen - who was formerly positive about the effort - confessed that Cambodia long-maintained ties with the new ASEAN members of ASEAN and rarely took harsh lines on Burmese regime. In 07PHNOMPENH534he notes that 'Burma has disturbed relations within ASEAN and with ASEAN partners', and 'Cambodia -- along with Laos and Vietnam -- have suffered.' According to Hun Sen, ‘pushing the regime too hard’ would only result in the regime moving closer to China and India, with no progress regarding democratization:

Any public discussion that could cause a loss of face to the Burmese leadership will not be productive, he noted. ... Burma can move forward, underscored Hun Sen, but one needs to find a way for the regime to do so without pushing too hard. In that event, Cambodia's efforts will not succeed, serving to push the regime closer to China and India and perhaps force a split within ASEAN, he said. The key to democratic progress is proper balance and a better understanding of the situation and the leadership dynamic in Burma, maintained Hun Sen.